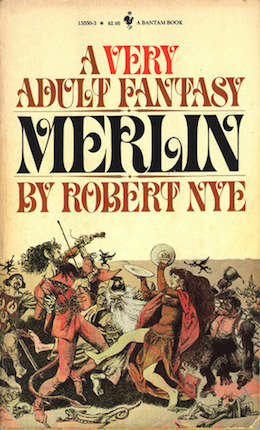

Large Gothic letters on the front cover of Robert Nye’s 1978 novel Merlin announce the book as “A Very Adult Fantasy.” To underline the book’s adult credentials, the book’s designer has set the “Very” in “Very Adult” in scarlet. The prospective reader can be forgiven for imagining a tediously bawdy assault on Arthurian legend, a story where “swords” are rarely ever swords, where rescued damsels are always willing, and where the repeated jokes get old fast. I love Monty Python and the Holy Grail, but I have no desire to see the Castle Anthrax scene crammed between covers and stretched into a novel.

If all I knew of this book were what I saw on its front, I would have left it on the shelf.

And yet I decided to pick this yellowing paperback off the shelf—largely because I’d heard praise for Nye’s other books, particularly his Shakespearean novel Falstaff—and because I’d had no idea Nye had written an Arthurian story. I found a very intelligent, very unconventional novel, but I also learned that the cover didn’t exactly lie: As we’ll see, this is a very naughty book. Yet for all the single- and double-entendres, lewd jokes and rude remarks that litter the page, what will first strike is this book’s thoroughly unconventional way of telling its story.

Merlin tells his story from inside his crystal cave. Or maybe it’s a magic castle. Or perhaps an enchanted tree.

He sees the past and the future.

Merlin tells much of his story in very short sentence-paragraphs.

Nye dedicates the book to Thomas Malory, author of Le Morte d’Arthur.

And to some Modernist authors he borrows stylistic tricks from.

This staccato prose works better at length than it does in a brief review.

So I’m stopping now.

Merlin’s structure is nearly as strange as its style: The story begins with Merlin’s conception, but doesn’t actually reach his birth for another eighty pages. This might seem a distraction from the main plot, but the enchanter is right to say his birth is of interest. After all, “My mother was a virgin. My father was the devil.”

The devils Nye gives us—Lucifer, Beelzebub, and Astarot—are a very talkative bunch, their conversation, alternatingly witty and obscene, comprises much of the novel. They discuss Freud and are proud of writing the Malleus Maleficarum; they bicker, mock, and collude on every occasion; they provide comedy and occasional horror. Educated as they are, they can quote scripture to their own ends; they’re also aware they’re in a book—they believe they’re writing it—and will even provide chapter citations when discussing past events!

Nye’s devils steal quotes from Milton (properly fiendish, they fail to attribute them), his inferno borrows from Dante’s, and his opening scene seems to have been inspired by a cryptic Shakespeare line about “leading apes in hell.” He also knows his Arthurian myth backwards and forwards, though he twists them at will. Seeing Nye’s variations on the various Merlin legends is one of the great pleasures of this book: If you’re familiar with the prophecy of the three deaths, or with Merlin’s tutor Blaise, or the story of Merlin establishing Stonehenge, you may well be Nye’s intended audience.

And here, with a discussion of the intended audience, I must return to the “Very Adult” label on the book’s cover. This is a very explicit book, full of pornographic tropes: There’s a great deal and a great variety of sex, presented at greater length and more graphic detail than anything else in the book. It would be easy to pick a few passages of panting, sighing, four-letter words, and female abasement and label Merlin misogynistic pornography, but that would ignore the book’s moral point. The ouroboros, the snake eating its own tail, appears throughout the novel; for Nye, the misogynist destroys himself after he has destroyed others. Merlin, sorcerer, voyeur, misguided son of the arch-fiend, is trapped more by his non-relationships with women than any crystal cave or locked castle. To him, all women are virgins or whores, distinguishable only by their degree of licentiousness or unworldly innocence. As he’s finally informed: “You started with gold, Merlin. You have turned it all into base matter, haven’t you?” Or, as Merlin admits, “I am a man turned inside-out.”

Nye’s Merlin is a misogynist, but that doesn’t mean he assigns any particular virtue to men. In the cases of Uther, Lot, Lancelot, and the wretched Friar Blaise, lust is the great motivator. Still, these men are afforded the tiniest bit of dignity: the other men in the story seem to be motivated by mere stupidity. The devil chorus of Astarot and Beelzebub comes off looking better.

I love to close reviews with wholehearted recommendations, but I can’t rightly do so in this case. Merlin is one of the strangest and most surprising books I’ve read this year. It begins before its proper beginning, proceeds in extended fits and brief starts, ends suddenly, and left this reader equal parts perplexed and satisfied. I’m very glad I plucked it from that dusty used bookstore shelf, but I’d have to know a friend’s taste very well before I recommended it to them.

A final aside: When Robert Nye died this July, Merlin made only a brief appearance in his various obituaries. One remembrance quoted at length from his poetry, while most others emphasized his most famous work, Falstaff. This isn’t surprising: These days, most papers don’t have room for long obituaries of somewhat obscure writers. But I wonder if Nye didn’t think this book was underrated; Arthurian tradition, however much he might make fun of it, evidently meant a great deal to him. The obituary noted that one of his surviving children was named Malory; another was named Taliesin, after the mythical bard in the earliest Arthur stories.

Matt Keeley reads too much and watches too many movies; he is helped in the former by his day job in the publishing industry. You can find him on Twitter at @mattkeeley.